Violette Leduc poses for a photo with her breakout work, La Bâtarde. Photo courtesy of Women Make Movies.

“To write is to prostitute oneself,” the French memoirist Violette Leduc declared. Her body of work -- which explores her illegitimate birth, sexual exploration, lesbian relationships, and unrequited love -- attests to her unabashed claim.

Equal parts self-loathing and self-aggrandizement, Leduc’s work is redeemed both by its honesty and by a generosity that offers up metaphorical riches and a decadence of detail. Although she began to write during World War II, the topics and styles she makes her own have a distinctly contemporary feel. Her work could rest between Lena Dunham’s Not That Kind Of Girl and Roxane Gay's Bad Feminist, although Leduc might be more audacious not just because the era in which she wrote but because of the odds she surmounted to do so.

Even now, it is a brazen act for a woman in many countries to speak openly about having an abortion. Just this month, American women offered up their abortion stories via live streams, write-in campaigns, and an amicus brief to the highest court in the land. If abortion is not the taboo a topic in France that it is in the U.S., it’s partly because of women like Leduc who signed the monumental “Manifesto of the 343 Sluts” and in so doing, paved the way for the legalization of abortion in France.

Although a feature film and documentary about Leduc’s life have added to her popularity in recent years, the groundbreaking writer remains largely unread outside of France. THE ALIGNIST’s Beenish Ahmed called up Columbia University professor Elisabeth Ladenson to talk about Leduc’s troubled life and unsung legacy -- but mostly, about her unsparing prose. Their conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, is below.

1. Here in the U.S., there’s been a flurry of memoirs from women writers in the last few years. I wonder if you think there's something that's distinctly feminine or even feminist about the tell-all kind of memoir that Leduc wrote.

I mean, the thing that is perhaps important to bear in mind is that when Leduc first started writing autobiographical narratives in the 40s, she was coming right after Jean Genet [...] who wrote about his childhood as an illegitimate child abandoned by his prostitute mother, being brought up by foster families, and then spending his formative years in [...] youth detention facilities. He wrote very candidly about sexuality, and particularly homosexuality.

He was promoted by Jean Paul Sartre and Leduc and he made a big huge splash and became very famous and Leduc was basically Simone de Beauvoir's equivalent “project.” [...] I think it's important to look at Leduc in terms of Genet because what you would now refer to as a tell-all memoir about sexuality [...] has become a “women's genre,” but in fact it [basically originated with men in France].

It’s important that right in the middle of the 40s while the war is still going on, Leduc doesn't start writing because she read Jean Genet. That's not in fact what happened. She was invited to write by another male writer -- another homosexual male writer -- named Maurice Sachs. The thing about Leduc is that she's on the one hand, a totally great feminist model and on the other hand a terrible, terrible feminist model.

2. Why do you say that?

First of all in terms of sexuality, Leduc's sexual preference was basically the people who were least likely to want to have sex with her. I mean, she was, to a certain extent, the female Genet [in that regard]. They both had this kind of poetics of abjection in which abjection is kind of eroticized. But of course he's a man and she's a woman, and they're also different people obviously, so they do this very differently. In his case, he basically manages to be both butch and femme at the same time and he just kind of covers all of the possible erotic identities, whereas what she does is that she goes after people who do not desire her. Gay men and straight women: those were her sexual preferences.

Simone de Beauvoir, who was one of her objects of adoration, wrote a preface La Bâtarde which she really [...] hits the nail on the head when she says [...] Leduc cannot deal with either absence or presence, basically she can't [...] live with them or without them, to phrase it in country music terms. She is just unable to bear either the presence or the absence of the beloved, and so, in fact what you see in La Bâtarde is that the real object of desire ends up being the reader. [Beauvoir justifies her conclusion by explaining that] the reader is at once absent and present, and the reader is basically the person who listens to her flood of narrative of abjection.

That evening I asked her what she had found to do with herself. ‘I pulled the curtains and made love to myself,’ she answered. I was shattered. What could I be jealous of in that? How could I not be enamoured of such frankness? It shocked me just how far apart we had moved. She vanished, with a certain fictive element, a shred of morality, a tattered remnant of modesty. Later I made love to myself with daring, perseverance, with immodesty, with studied postures. I closed the curtains on Thursday afternoon, I stretched out on the divan as she had stretched out on it. I wanted to imitate her in order to have my revenge on her.

-- from Mad in Pursuit by Violette Leduc

A woman reads outside of the iconic Paris bookstore, Shakespeare and Co. Photo by Christine Zenino via Wikimedia Commons.

3. You brought up Jean Genet who also wrote about homosexuality and sexuality. He received far more acclaim than Leduc did during her lifetime, and even now he’s far more widely read. Why didn't Leduc see the same sort of praise or attention, do you think?

There are a whole bunch of ways to answer that. [...] [One way is that] Leduc is obsessed with two basic problems: one is that she's illegitimate and the other is that she's ugly. All of her works are completely obsessed with these two problems, these two original wounds and basically, I think, how can I say this...Genet is a more appealing figure than Leduc.

Leduc must have been absolutely unbearable to deal with -- even reading her is kind of unbearable, whereas Genet goes swaggering around. Genet is more attractive in the way that a guy who goes swaggering around is more attractive than a woman who is, basically, a fountain of narcissistic self-pity which is, among other things, what [Leduc] is. What's amazing is that she turned this into absolutely fascinating narrative. I do think that Genet is just [...] a really attractive figure in that he's kind of masculine [and] feminine. He's an artist and he's also a thief -- he's got every conceivable corner covered, plus, I think, that the difference between them is really neatly observable in the way that [...] they address the reader. [...]

Genet [...] addresses the reader, not in a condescending way exactly, but he basically [tells] the reader, “You're a nice comfortable [...] heterosexual, bourgeois leftist who wants to get a thrill out of my experiences but you'll never really know what I've gone through,” whereas Leduc kind of appeals.

Leduc says says “lecteur, mon lecteur” and you can imagine her sort of caressing her imaginary reader on the sleeve. She really wants something from the reader, whereas in a way, Genet plays the old joke about the sadist and the masochist: the masochist who says hit me and the sadist who says no. He kind of plays that game with the reader, whereas Leduc really wants the reader to come and complete her in some way.

As a result just like someone who goes swaggering around and is a little bit sadistic will always exert more fascination than someone who wants to appeal. I suppose one could also say that it's because of institutionalized misogyny that he's more read than she is, but I think that [their very different voices] is actually more accurate.

4. Well, Leduc writes in very vivid details about her sexual encounters, including lesbian ones. I wonder how revolutionary that was at the time, do you think that's a part of it, that the world was not ready to read about female sexuality in that way?

I suppose to some extent that may be accurate but you have to remember that lesbianism is all over the place in French literature in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. It's male homosexuality and what Genet writes about -- he writes quite explicitly about stuff that had never been written about in mainstream French literature. [...]

The endless literature about lesbianism in the 19th century and the early 20th century was mostly written by men but not all...That Genet seemed to have an easier time getting an audience than Leduc is weird [in that regard].

In [the short story] “Thérèse et Isabelle,” and [her memoir] La Bâtarde, Leduc recounts the same incident [of a first sexual encounter between two schoolgirls] that had been removed from [an earlier book called] Ravages. In La Bâtarde, which was her big breakout book [published] in 1964, she goes into all kinds of detail and it's quite -- the word I'm hesitating to say is pornographic. [...] It's quite explicit and it doesn't look all that different from pornographic approaches to the same stuff so it's not totally divorced from that pornographic tradition. [...]

It was too explicit for Gallimard [France’s most prestigious publisher] but I also learnt something interesting about Gallimard when I was doing research about The Well of Loneliness, Radclyffe Hall's 1928 book that was censored. It was a novel about what we would now call a transgender or transsexual character, but lesbian character as she was viewed at the time. It was censored in England for 20 years out of a very notorious trial. That book was in fact the first novel by a woman published by Gallimard.[...] In 1932, [Gallimard] published the translation of The Well of Loneliness, which doesn’t have any explicit sex scenes [although it does take] lesbianism as a topic. Lesbianism as a topic was certainly always kind of scandalous but it was not something hadn’t been talked about endlessly in literature before them.

Isabelle pulled me backwards, she laid me down on the eiderdown, she raised me up, she kept me in her arms: she was taking me out of a world where I had never lived so that she could launch me into a world I had not yet reached; the lips opened mine a little, they moistened my teeth. The too fleshy tongue frightened me; but the strange virility didn’t force its way in. Absently calmly, I waited. The lips moved over my lips. My heart was beating too hard and I wanted to prolong the sweetness of the imprint the new experience brushing my lips. Isabelle is kissing me, I said to myself. She was tracing a circle around my mouth, she was encircling the disturbance, she laid a cool kiss in each corner, two staccato notes of music on my lips; then her mouth pressed against mine once more, hibernating there. My eyes were wide with astonishment beneath their lids, the seashells at my ears were whispering too loud. Isabelle continued: we climbed rung after rung down into the darkness below the darkness of the school, below the darkness of the town, below the darkness of the streetcar depot. She had made honey on my lips, the sphinxes were drifting into sleep again. I knew that I had needed her before we met. Isabelle thrust back her hair which had been sheltering us.

-- from La Bâtarde by Violette Leduc

5. But it was mainly, if I'm not wrong, male writers who were writing about lesbian relationships and trysts, no?

Yes, that's true, well, yeah I mean there was also Colette but of course she published that under her husband's name. Not Radclyffe Hall, but yes, you're absolutely right. [...] The thing is that you can never underestimate the force of misogyny in French literature.

6. Leduc was amongst the first to write about lesbian relationships, and amongst the first to write about getting an abortion which she did at a time when it was still illegal to get an abortion in France. How was her revelation received and was she then treated as something of an activist or a feminist as a consequence?

Leduc was really amazing in that there was just absolutely nothing that she wouldn't write about. [...] I'm afraid I don't really know that much about the reception of that but I mean, certainly Simone de Beauvoir was one of the notorious “343 sluts” who [signed a manifesto in 1971 stating that they] had had abortions. Simone de Beauvoir was one of them, and Catherine Deneuve. They were all these kind of mainstream women who came out as having had abortions.

A lot of those names were really, really kind of shocking because they were women who had careers as writers and actresses and all kinds of public figures who basically came out of the closet as having had abortions. That was a very important moment in the history of French feminism and also in the history of the pro-abortion movement.

I'm not sure how much of an activist [Leduc] ever really was; her motivations were sort of political secondarily. She was mostly trying to live her life. She stumbled into being a political activist because so much of her identity was based on issues that were feminist issues or social issues. [...]

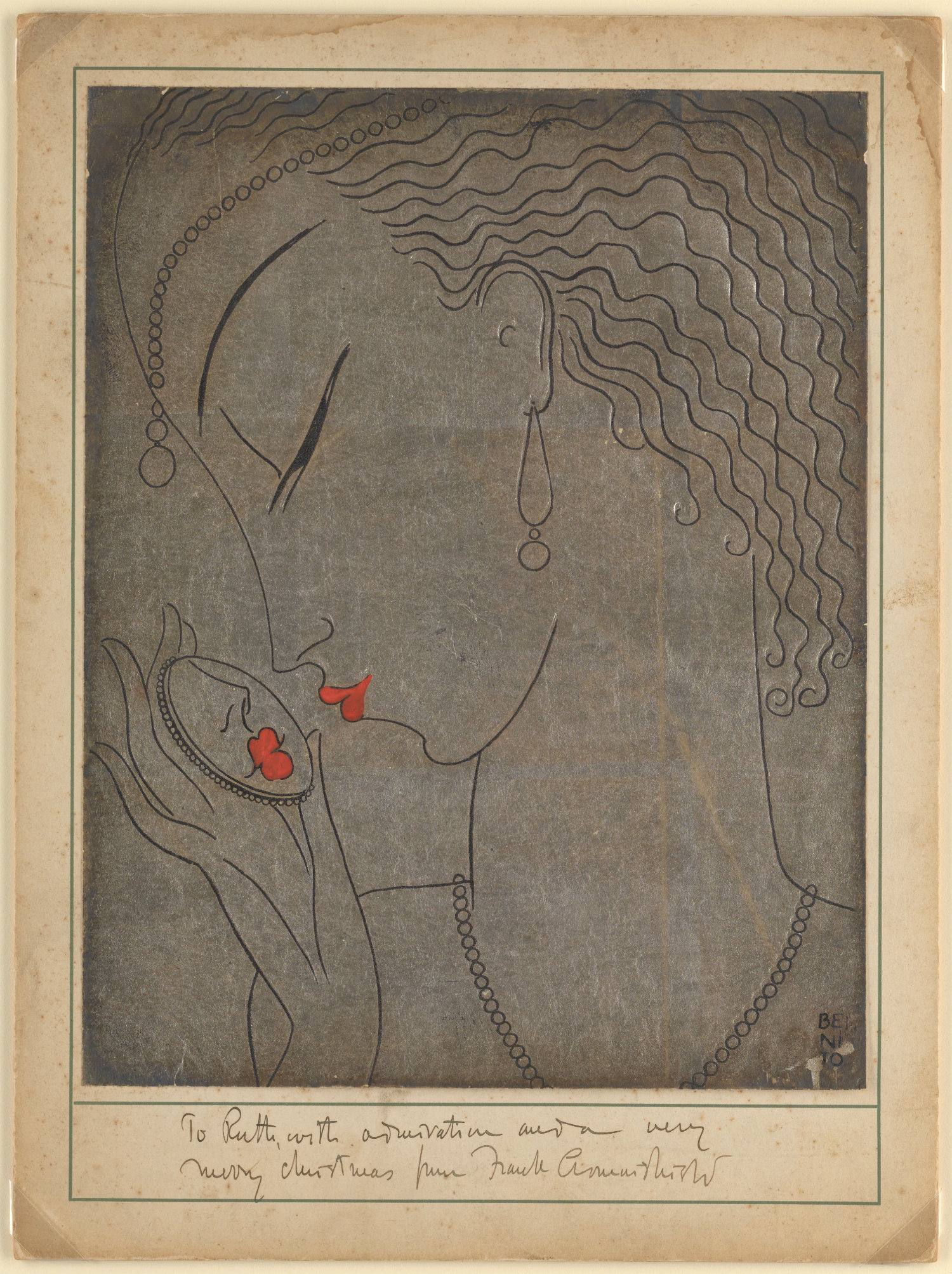

An illustration for a dance division by Jerome Robbins. Image via The New York Public Library digital collections.

She was born illegitimately. Her mother was a maid working for a wealthy family and she got knocked up by the son of the family. He wanted nothing to do with her or her child. His mother was very fond of [Leduc’s mother] and tried to get her...to explain why she was leaving [after she became pregnant], but she wouldn't. She was too loyal to the family and she left and had [Leduc].

If you read the books about [Leduc’s] childhood it's clear that her mother [made her feel that she] came into the world as the incarnation of how badly everything is organized for women and the working class, but particularly women of the working class. She got pregnant and it was her problem. At the time -- Violette Leduc was born in 1907 -- being illegitimate was a really big deal, which is almost hard to remember now, but the 20th century really changed everything completely.

Her ugliness is kind related to that. [It was] kind of the physical manifestation of [her feeling that] she just should never have existed. [...] When she was at school, everyone knew she didn’t have a father [...] just because of the social organization of childhood. When she became an adult, being illegitimate was no longer visible everyday. What took over the role of reminding her that she just didn’t have a place in the world was ugliness, it seems to me.

I wanted to be more beautiful. Hermine started buying Vogue and Femina and Le Jardin des Modes again. I learned by heart the benefits to be derived from tonics and astringents -- implacable enemies of the enlarged pore -- from cleansing cream and nutritive cream, from orange juice and apricot powder. Head in hands, I pored anxiously over experts’ advice and advertisements alike. Wrinkles, crow’s feet, flaking skin, blackheads, cellulitis, a list as terrible as the dreadful warnings of Jeremiah himself. Page after page, I read and reread my blackheads, my wrinkles, my enlarged pores, my falling hair. Page after page I suffered and would not look at myself. [...]

-- from La Bâtarde by Violette Leduc

7. It’s interesting that Simone de Beauvoir -- who herself wrote so much about how women needed independence in social, economic, and sexual terms -- would be the one to bring Leduc’s work to the world. So many are assigned to read Beauvoir in college. Her name comes up often in philosophy, women’s studies, literature -- and yet, no one seems to know much about Leduc. How widely is she read these days?

Leduc seems to be having a bit of a renaissance these days. There's been two biographies written of her in the last few years, there's two films, her works are all in print. The kind of no-holds-barred female -- not confessional so much -- but intimate resolutory autobiographical narrative [that Leduc wrote] is very popular in both France and America [right now].

[There are] contemporary French writers like Christine Angot whose writing is very much like that of Leduc. I think, that there’s also male versions, like, I don't know, Karl Ove Knausgård.

The analogy between Violette Leduc and Karl Ove Knausgård is an extremely unlikely one, I realize, because of their extremely different moments and formats and lives and countries of origin but Knausgård said somewhere, basically, that the whole point of writing is to write about what you feel ashamed of. In a way, I think it's probably not that far removed from [the idea that] to write is to prostitute oneself [as Leduc has said].