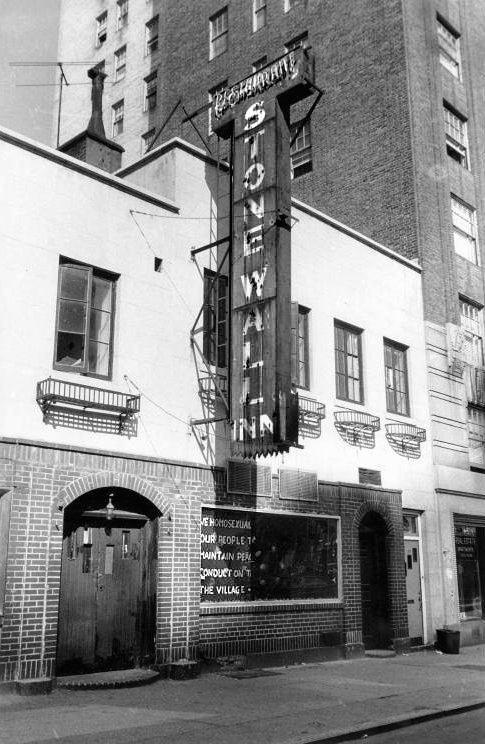

STONEWALL INN, SITE OF THE 1969 STONEWALL RIOTS, NEW YORK CITY. IMAGE FROM DAVID CARTER'S STONEWALL: THE RIOTS THAT SPARKED THE GAY REVOLUTION VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

BY BEENISH AHMED

“To fully grasp the unique horror of what happened inside Pulse — a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida that became the site of the worst mass shooting in America — you have to understand the outsize role that gay bars play in the history, lives and imagination of gay people,” Michael Barbaro, a reporter for the New York Times, wrote in an op-ed after a gunman named Omar Mateen killed 49 people and injured even more in a rampage on Sunday.

For Barbaro, it was a gay bar in Washington where he finally felt he could come to terms with his sexuality — and come out about it.

The broader importance of venues for LGBT people to freely associate and build community can be understood through the fact that a 1969 police raid on the New York City gay club called the Stonewall Inn led to the first major protest for equal rights for LGBT people in America. Gay bars have long been — and continue to be as this weekend’s attack made clear — targets of violent extremism.

Assailants like Mateen exploit the frenzied joy of the dance floor and turn it into frenzied horror. And so the attack on Pulse was not just a brutal massacre and a violation of a safe haven, but a desecration of a place of celebration for a community still engaged in very real battles against marginalization, discrimination, and all out violence.

“[G]ay bars are more than just licensed establishments where homosexuals pay to drink,” Richard Kim, the executive editor of The Nation, wrote in a moving piece soon after news of the carnage in Orlando broke. “Gay bars are therapy for people who can’t afford therapy; temples for people who lost their religion, or whose religion lost them; vacations for people who can’t go on vacation; homes for folk without families; sanctuaries against aggression. They take sound and fabric and flesh from the ordinary world, and under cover of darkness and the influence of alcohol or drugs, transform it all into something that scrapes up against utopia.”

Here are five novels that capture that almost-utopia that was so horrifically attacked last weekend.

Dancer from the Dance

“It’s the Catcher in the Rye of gay literature,” William Johnson of the Lambda Literary Foundation, an organization that promotes LGBT literature, said of Dancer from the Dance.

The book is an ode to the club and those for whom late night drug-filled discos are the essence of existence. The story follows two characters — Anthony Malone, a lawyer who leaves his career for that scene, and Andrew Sutherland, a drag queen and speed fiend — as they navigate a world dedicated to pleasure. It’s a world that offers them an equality unknown outside of the thrashing lull of syncopated beats and sweaty hook-ups.

“They lived only to bathe in the music, and each other's desire, in a strange democracy whose only ticket of admission was physical beauty — and not even that sometimes,” Andrew Holleran wrote in Dancer from the Dance. “All else was strictly classless: The boy passed out on the sofa from an overdose of Tuinols was a Puerto Rican who washed dishes in the employees' cafeteria at CBS, but the doctor bending over him had treated presidents. It was a democracy such as the world — with its rewards and its penalties, its competition and snobbery — never permits, but which flourished in this little room on the twelfth floor of a factory building...because its central principle was the most anarchic of all: erotic love.”

“A lot of people were frustrated with the book because it's a book about circuit queens or clones, but it treated this particular community with a sensitivity and a humanity and a sense of humor,” Johnson told THE ALIGNIST in a phone interview. He was careful to note that those killed at Pulse, the Orlando gay club, are likely from a very different milieu for the most part. Still, he said, “The feeling of being in the club is the same whether you’re a circuit boy or a club goer — the joy and the community and the music and the power of losing yourself with a large group of people — I think those feelings are the same. And Dancer from the Dance really captures that, even though it’s about a very specific [type of] gay circuit boy.”

Holleran was aware of that divide and made it known to his characters, as well. At the end of the novel, Sutherland walks through a Pride Parade in Central Park and realizes that he hardly knows any of the city’s LGBT community: “'I used to say there were only seventeen homosexuals in New York City and we knew every one of them, but there were tons of men in that city who weren't on the circuit, who didn't dance, didn't cruise, didn't fall in love with Malone, who stayed home and went to the country in the summer. We never saw them. We were addicted to something else.'”

The Young and Evil

Called “the first modern unapologetic thoroughly gay novel,” The Young and Evil is follows “a queer group of friends in New York City spends much of its time becoming uproariously drunk at parties, swapping beds and apartments, avoiding the hostile attentions of both the police and the sailors they cruise in the park, eating on the cheap at all-night ‘coffeepots,’ generally looking fabulous in make-up and gowns, and occasionally creating art.”

When asked about the controversy that ensued after the book was first published in 1933, Charles Henri Ford, who wrote the novel along with Patrick Tyler said, “It was simply banned in America...You can't imagine how puritanical America was in those days.”

The book was reissued in 1960, and has since become a classic work of gay literature.

City Of The Night

“I have never stopped reading it,” Charles Casillo, a writer, actor, and producer, wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books upon the 50th anniversary of its publication. “Although it was long after the original publication, through City of Night Rechy taught me that my feelings of isolation could be released, that my experiences could be written. It was Rechy who showed me that no subject matter is taboo.”

The novel, which follows a gay prostitute or “youngman” who Rechy closely and unabashedly identified with, was an instant success. It made the New York Times’ bestseller list before its official publication date and won sweeping mainstream approval — even if its critical reviews were mixed.

“The fact that I closely identified with the narrator-hustler disturbed some people,” Rechy told Casillo in 2013. “Not every writer becomes a hustler on the streets and then writes about it! I think that focused identification on the narrator-as-hustler has unfairly extended at the expense of viewing me as a writer.”

Stone Butch Blues

“‘Nobody ever flirted with me outside a bar before — I mean in the real world, you know? It made me feel normal.’” Jess Goldberg, the gender non-conforming protagonist of Stone Butch Blues confesses to her crush, Theresa, who made a move on her at the factory where they both worked. The conversation takes place at Abba's — the only gay bar in Buffalo where much o the story is set.

The line suggests the divide between safety and uncertainty drawn between what Goldberg sees as the “real world” and the world in which she is free to be herself: a butch lesbian, on or off hormones, whether she “passes” as a man or settles into her own person free from such binaries.

“The bar functioned not just as a safe space but one of the few spaces where you could be yourself,” Yetta Howard, a professor of English and Comparative Literature who focuses on queer literature at San Diego State University, told THE ALIGNIST in a phone interview. “That’s a huge part of the importance of the bar not only in terms of that sense of belonging, but also these were places where you’d find the family that you didn’t necessarily have in the outside world.”

It’s at Abba’s that Jess meets Butch Al who becomes a sort of mentor to her in the ways of queer identity.

“[T]he depth and beauty of Stone Butch Blues comes from the way Feinberg takes the reader down the path of realizing what butch identity means — and what safety and self-acceptance inside that identity means — with her,” according to The Atlantic’s Shauna Miller who wrote a remembrance of the book upon the passing of its author, Leslie Feinberg, in 2014. “Jess's identity is so much more than her appearance. It's more than her choice to work in a male-dominated factory world. It's more than those simple and severely punished offenses against both womanhood and manhood. It's more than the fistfights with other butches as a desperate attempt at intimacy, more than disappointing her great love, Theresa, with her emotional and intimate distance. By the end of this book, butch identity comes from letting love's light trickle through a crack in the armor. But first the reader needs to understand where all the armor came from.”

That understanding can only come from following Jess on her journey to settle into her identity — and is written in a way so empathic that it offers itself up as an anecdote to the homophobia and transphobia so many characters in the book lurch at her.

Feinberg hirself meant the book to be a “call to action.”

“[With] this novel I planted a flag: Here I am—does anyone else want to discuss these important issues?” ze said. “I wrote it, not as an expression of individual ‘high’ art, but as a working-class organizer mimeographs a leaflet.”

Download a free copy of the book here.

Valencia

“I sloshed away from the bar with my drink, sending little tsunamis of beer onto my hands, soaking into the wrists of my shirt. Don’t ask me what I was wearing. Something to impress Whats-Her-Name, the girl I wasn’t dating. She had a girlfriend. She didn’t need two.”

So opens Valencia, Michelle Tea’s account of her sexual misadventures and wild stabs at love in grungy, 90s San Francisco. The autobiographical novel catalogues encounters with a woman who brandishes a knife in bed and another who stays obstinately clothed in the midst of intimacy, among others.

“It centers itself around the...club scene* which was one of only a few seven day a week lesbian bars,” Howard of San Diego State University said. “It really had its own kind of queer subculture.”

The book documents that subculture, but Valencia is about more than that, too.

“It’s about a kind of queer way of being that wasn’t beholden to heteronormative structures or a mainstream gay community, because at that time you did have an idea of gay identity that was more in line with assimilating into mainstream culture,” Howard said. “Valencia is anything but that. It shows queerness as an almost punk ethos. You have a lot of sex. You have a very subculturally specific way of being queer.”

Tea has been referred to as a “kind of pop ambassador to the world of the tattooed, pierced, politicized and sex-radical queer-grrls of San Francisco.” She opened her world up for readers and offered a tour of the individuals and institutions set apart from mainstream America that nonetheless forged a part of its history.

“In 2016, we might have nostalgia for [lesbian and gay clubs]* because those places are getting harder and harder to find in a city like San Francisco. That’s why it’s important for a club like Pulse to exist in Orlando,” Howard said. “It’s still important for people to find those spaces even if they might not mean the same thing in terms of safety as Abba’s in Stone Butch Blues. It doesn’t mean the same thing in terms of safety but it symbolizes something really important for queer people, even now.”

*CORRECTION: This article has been updated. Specific references to The Lexington, a now shuttered lesbian club in San Francisco, have been deleted following a message from from Valencia author Michelle Tea who said she wrote the book before The Lexington opened.