BY BEENISH AHMED

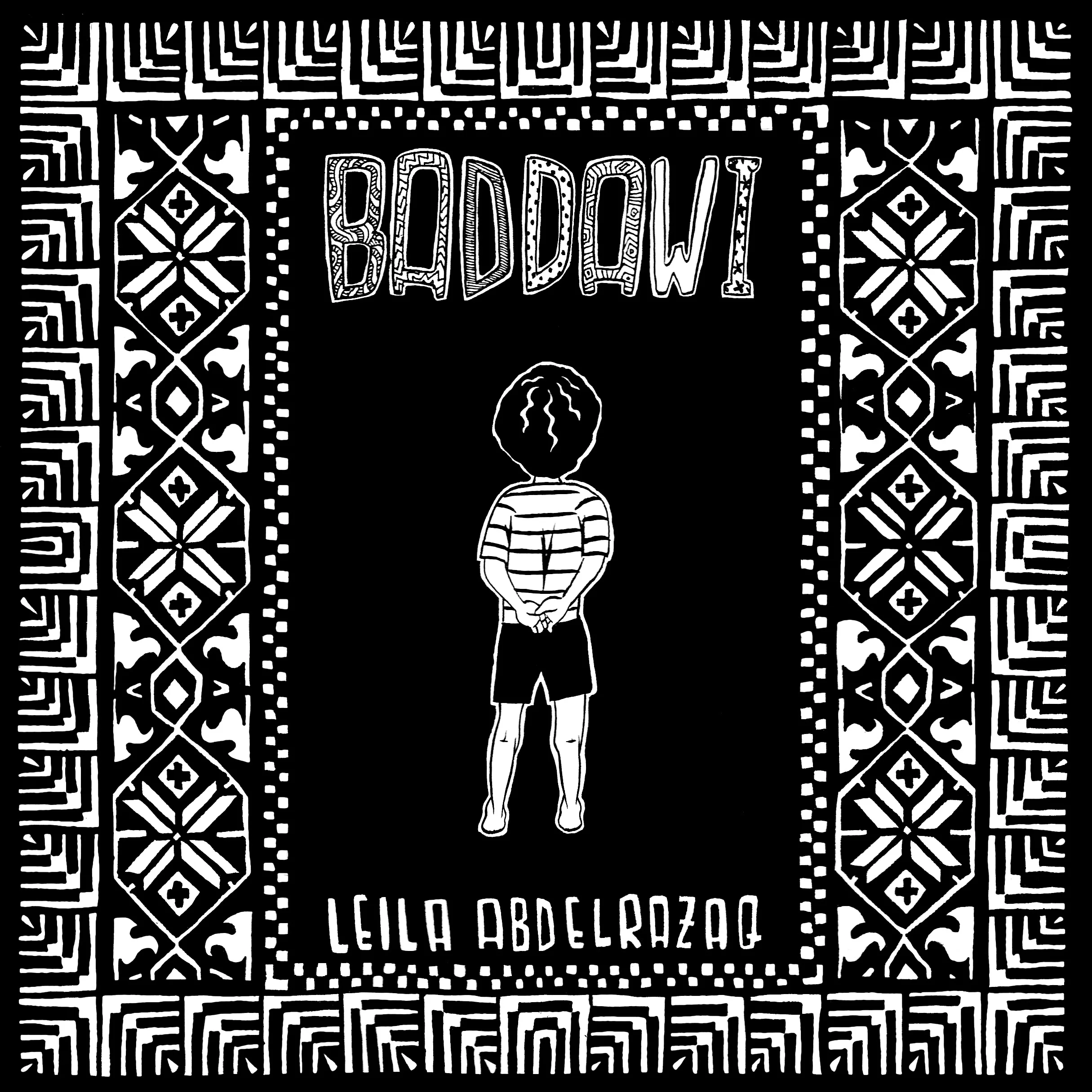

Leila Abdelrazaq is 22 years old and the author of a new graphic novel. If the lanky and freckled recent college graduate is unfazed by her success, it’s because she never dreamed of writing a book — much less one set to incisive black and white ink images. As a theater and Arabic Studies major, she never even studied art formally, but in her book Baddawi, Abdelrazaq depicts the life of her father led as a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon with striking detail, rich narratives, and a nod to history.

“I was interested in illuminating [my father’s story] and also finding out about my family’s history because I grew up without many opportunities to go to Lebanon or anything like that until I got older,” the Chicago-born, Seoul-raised artist said in an interview with at a trendy Washington, DC coffee shop. “I think it’s a product of diaspora where you [as the child of immigrants] recognize that these stories are unusual in a sense, even though they are really common within a community.”

It was returning to Chicago and connecting with others similar backgrounds that led her to explore her own family’s roots -- especially because she felt that most people she encountered lacked a real understanding of what it meant to be a Palestinian refugee.

In filling that gap, Abdelrazaq sees her work as political -- and acknowledges that its a product of her own views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“When you say, 'I’m Palestinian,' whether you like it or not, that’s politicized,” she said as she sipped from a black mug of black coffee. She let out a dry laugh before she described how questions about her ethnicity so often seem to open up as political debates.

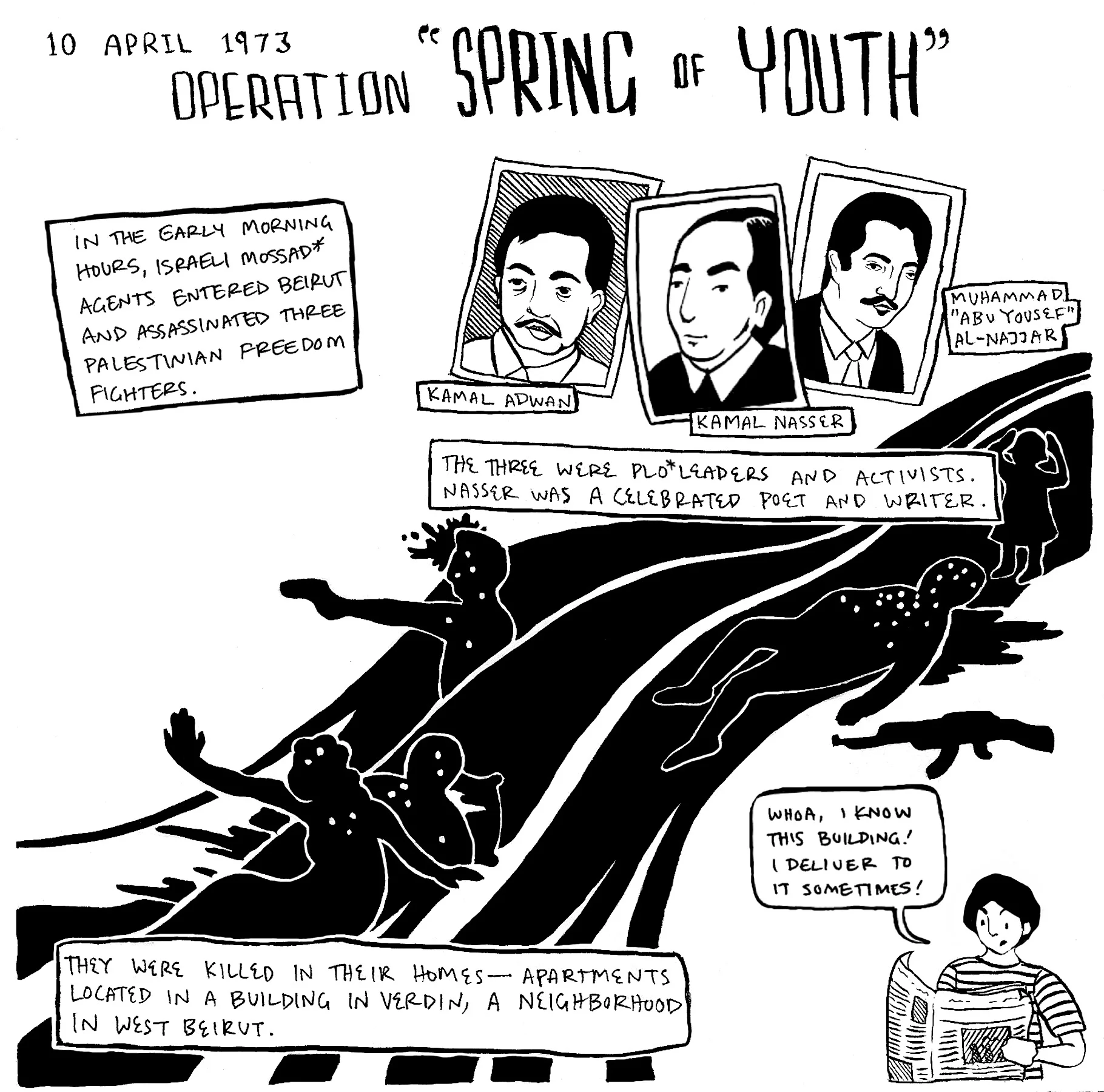

While such exchanges are not always welcome, Abdelrazaq is not someone who shies away from sharing her opinion. She sees herself as “a political person” and her political views are easy to identify in Baddawi whether in her choice of words: in the book, uses the term “freedom fighters” not the more innocuous “militants” and, in speaking with THE ALIGNIST, Abdelrazaq referred to the ouster of Palestinians from what is now Israel in 1948 as “ethnic cleansing.”

In this way, she came to see her graphic novel as a political project, meant to showcase a specific perspective as they evolved through the specific events that come to make up a life.

Given what she sees as the persecution of Palestinians by Israelis, Abdelrazaq said, “Just the fact that you are existing as Palestinian and owning your Palestinian history is a political act. In that same vein then, telling your stories is also a political act, because you’re keeping your history alive in the face of something that trying to erase it or destroy it.”

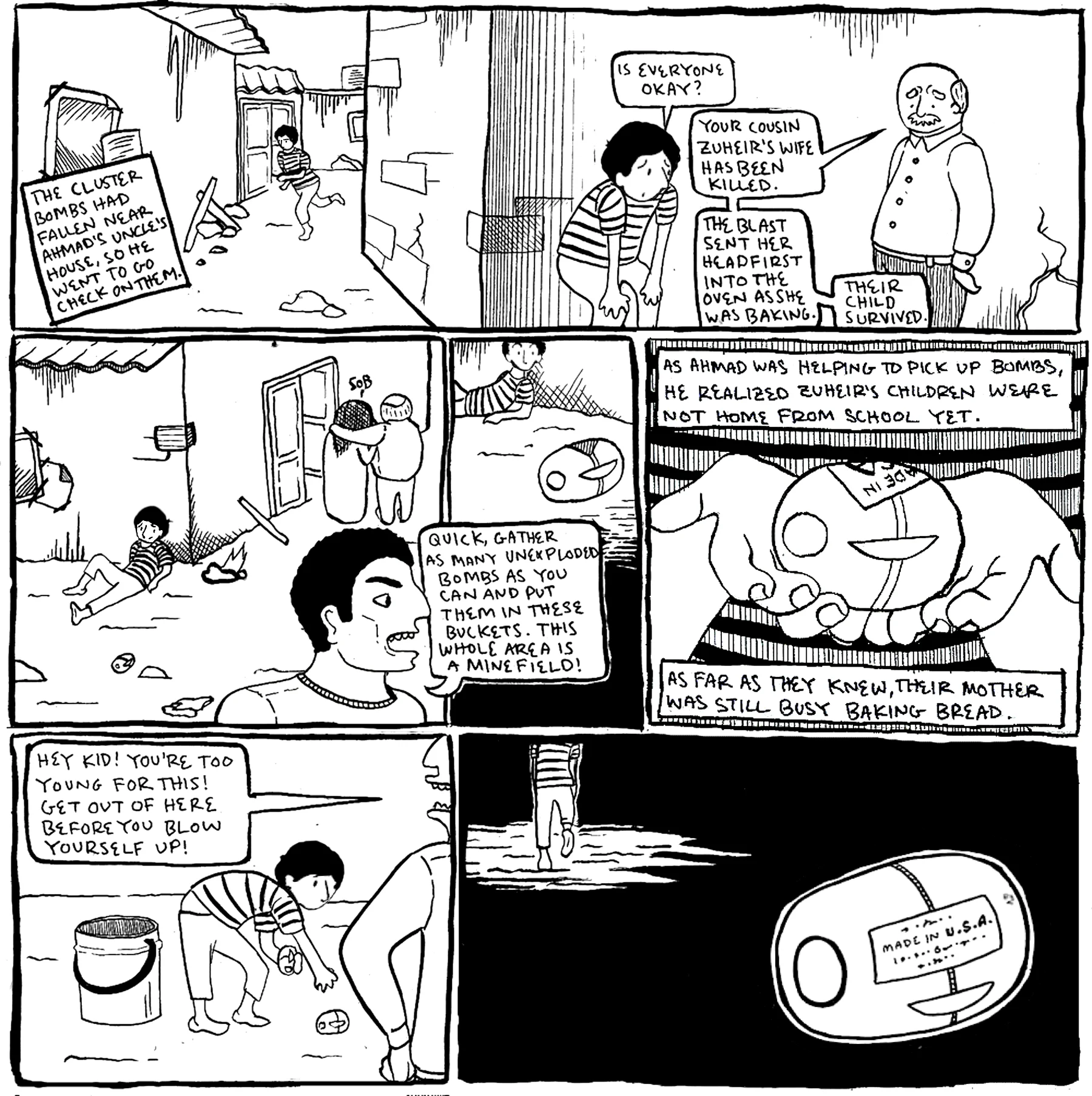

And Abdelrazaq spares no country of critique. Although she harshly judges not just Israel but also Lebanon harshly for its treatment of Palestinians, and offers a critical look -- though its often subtle -- of the United States, the country where her father first immigrated to when he left Lebanon.

All images from Baddawi are courtesy of the author.

Although the project evolved into a deliberately polemical one, it didn’t start out that way.

“I was posting [illustrated] anecdotes that my dad had told me and my brother…and then posting them to a blog and my Facebook,” she said. Eventually, Just World Books, a Middle East-focused publishing house based in Charlottesville, VA, got in touch and offered her a book deal.

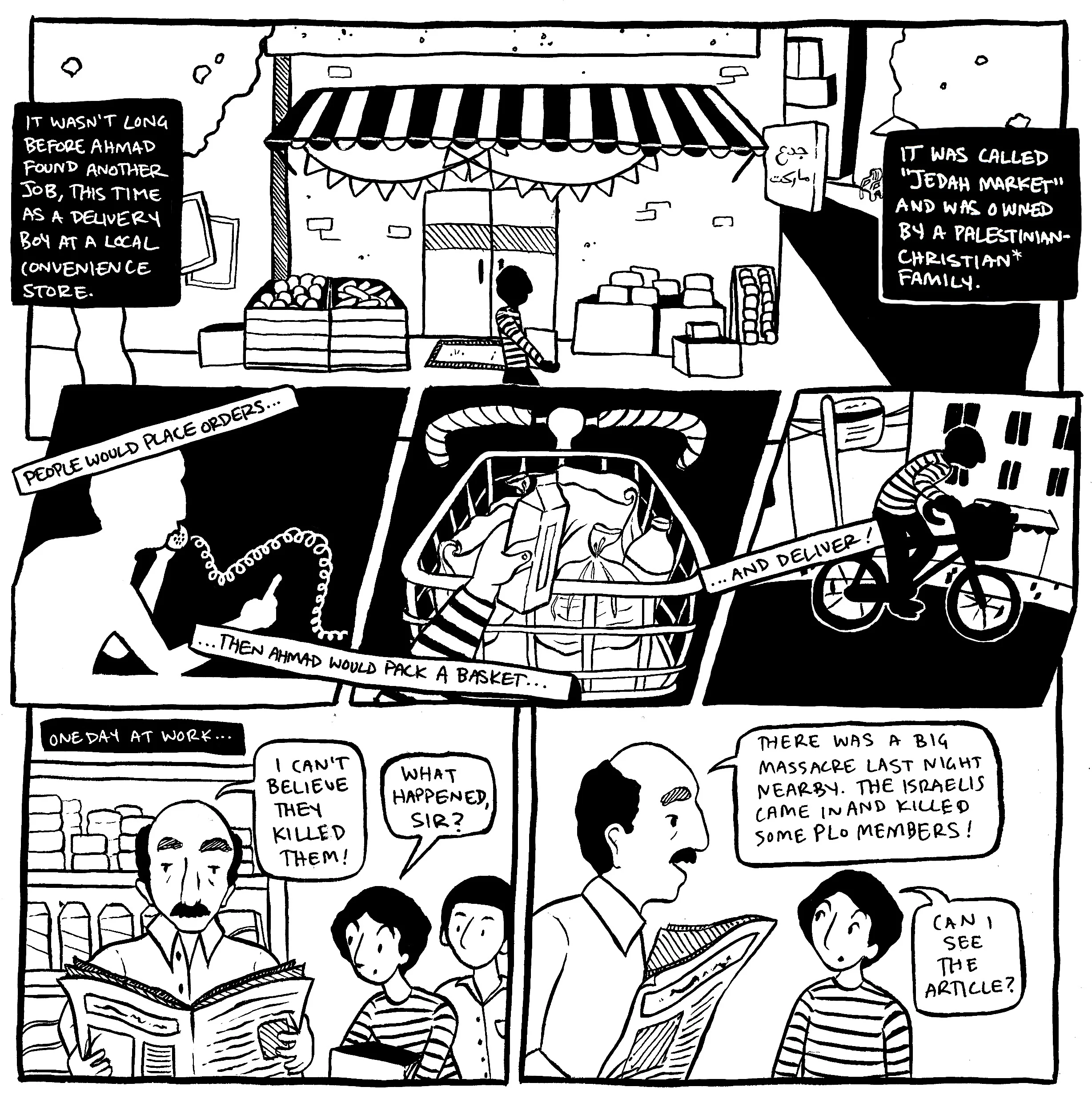

Abdelrazaq then set to work creating a cohesive narrative out of the vignettes she’d been drawing, which meant doing a lot of research not just into her father’s story as a young man in the Baddawi refugee camp in northern Lebanon, but also into the historical events that it was set against — which wasn’t always easy.

“I would ask him about specific political moments that I wanted to include in the book…I would ask him, do you remember that? How did you feel? And he would just be like, ‘Eh, I don’t know. I don’t remember that.’” Abdelrazaq recalled. “He knows it happened, obviously, but he doesn’t remember what he was doing on that day or how he felt about it as a kid, and I think that makes sense, because as a kid, you’re just responding to what’s directly around you. So when there was a massacre in a Palestinian refugee camp, maybe he heard about it, but he wasn’t there.”

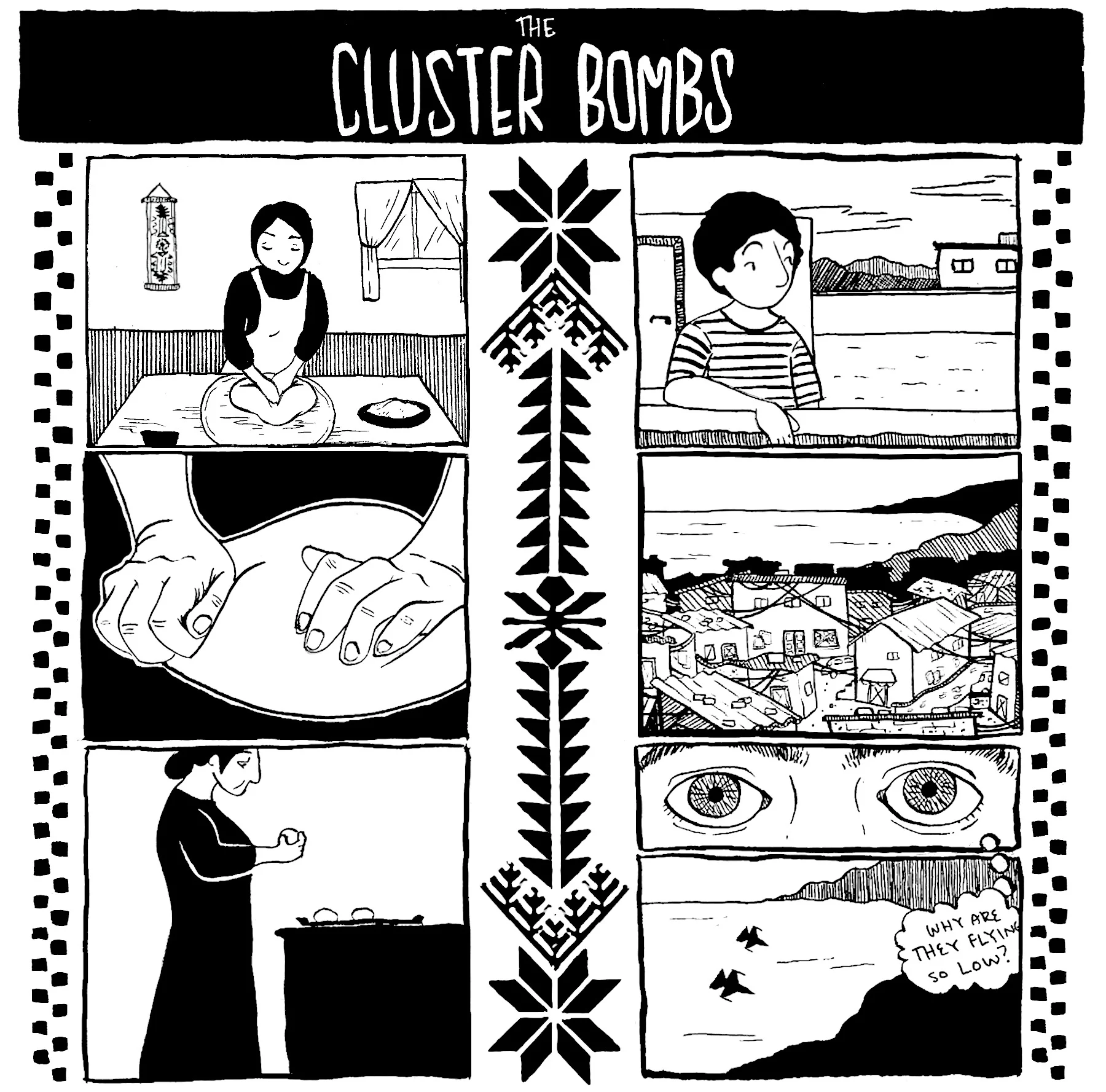

At other moments, however, Abdelrazaq seamlessly wove her father Ahmad’s experiences with events related to the Lebanese Civil War which lasted from 1975 through to the early 1990s.

“I was interested in how Lebanese history became Palestinian history, because Palestinian history, just like Palestinian people, is no dispersed all over the world,” she said. “So just adding a personal spin [to major events in Lebanon] was important to me.”

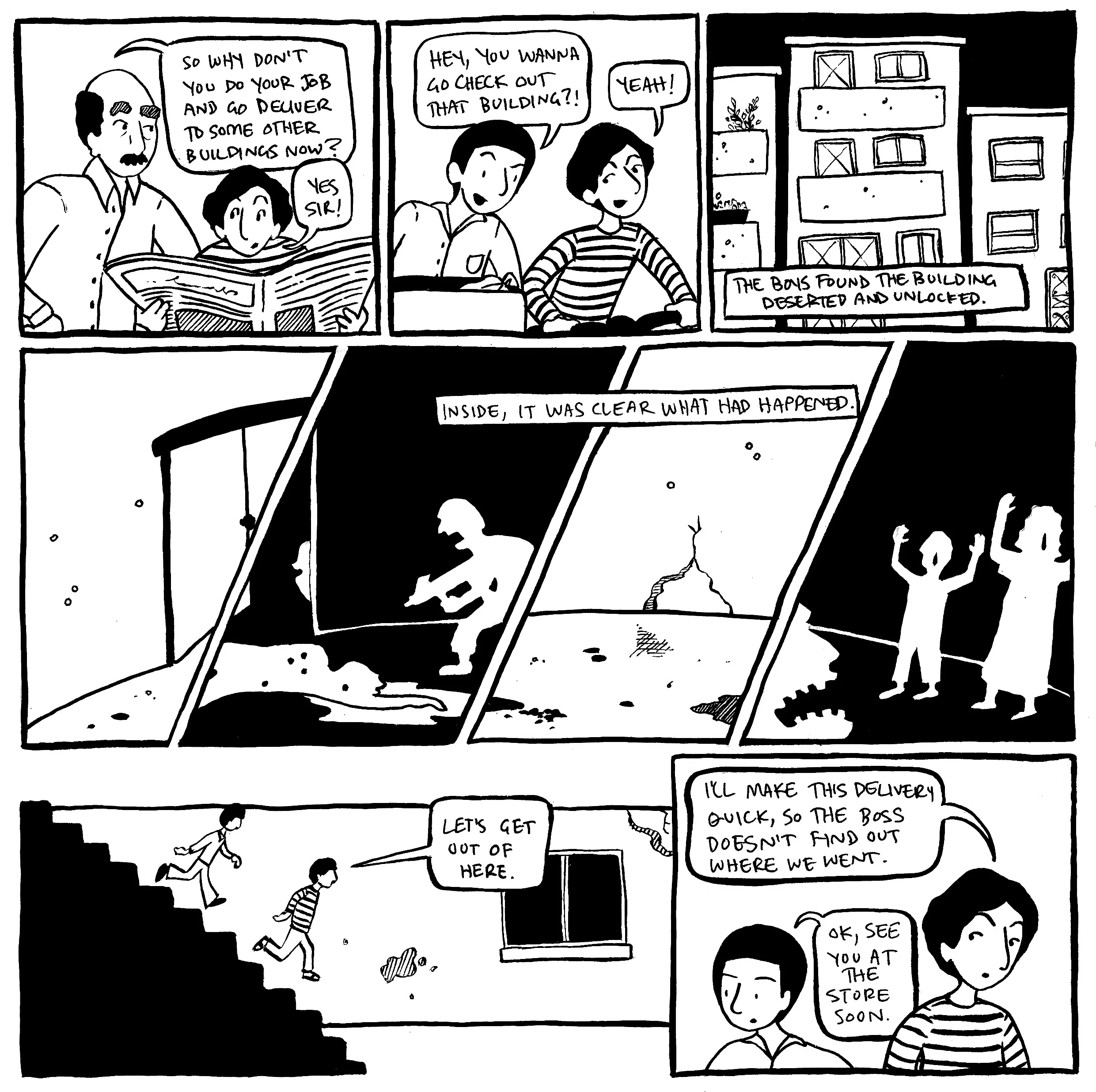

The book provides a human face to the often overlooked experiences of refugees. It also offers a glimpse into how a young man experienced conflict in ways that betrayed his youth, but also, perhaps, forced him to grow up.

In one part of the book, for instance, Ahmad, found out that building he often delivered groceries had been bombed. Curious, he and a friend go explore the site, but they seem to be overwhelmed and leave the site without talking about they saw.

For Abdelrazaq, working on Baddawi was a way to learn more about her father’s early years — from his pick up soccer games to his teenage crushes. But in doing so, she came to learn a lot more not just about history, but culture too.

Abdelrazaq decided to incorporate everything from motifs from traditional Palestinian embroidery to her grandmother’s recipes into the book in order to provide a fuller picture of the cultural context her father emerged from — and to honor it through her own work.

“I looked at a lot of different embroidery designs and learned more about Palestinian embroidery,” she said. “I asked my dad, because he would always talk about how my grandmother made za’atar, and so asking him how she made it, was also a way for me to learn about my culture as well which was kind of cool.”

The embroidery dances across the cover of the book, which has an image of a young man at its center — one who resembles the stance of Handala, a character created by the noted Palestinian political cartoonist Naji Al-Ali. In Al-Ali’s cartoons, Handala is always shown with his back-turned and his hands folded as a sign of protest what he sees around him. Stunted at the age of 10 when Al-Ali himself fled Palestine and became a refugee, the character has become a faceless symbol to the nearly 750,000 thousand Palestinian refugees forced to leave their homes in what what became Israel in 1948.

“Part of [my project] was not drawing Handala’s face but giving a multiplicity of faces or trying to represent the way my dad experienced [the camps] instead of this faceless image of people who are so sad all the time,” Abdelrazaq said. “Just reminding people that there are rich communities [there].”

While she drew a lot of inspiration from Naji Al-Ali, whose works she developed a deeper understanding of through working on her book, Abdelrazaq noted that the most common comparison she’s gotten for Baddawi is to the Persepolis books by Iranian-French graphic novelist, Marjane Satrapi.

“I think that’s a fair comparison, but one that’s just because of the subject matter and the style, which is similar – but also that style is super common. It’s not so unique,” Abdelrazaq said.

While many would be apprehensive about a book written on their lives by a family member, Abdelrazaq said the “fear and nervousness” her father felt about her project had less to do with how accurately she told his story and more to do with how others might receive it.

“[There’s a] stigma against Palestinians in Lebanon which I think stuck with him,” she said — and that was only compounded with discrimination against Arabs and Muslims in the United States where her father eventually moved before shifting his family to South Korea.

“But at the end of the day,” she said, “he’s happy, and glad that I care about Palestine and my family’s history.”

That reaction has been reflected by other Palestinians who have read the book which came out earlier this month.

“I think, for all Palestinians, it just gives us hope when we see each other still engaging with our history even though we’re in diaspora or far away from everything,” Abdelrazaq said.

[NOTE: A version of this story originally appeared online on ThinkProgress.org.]